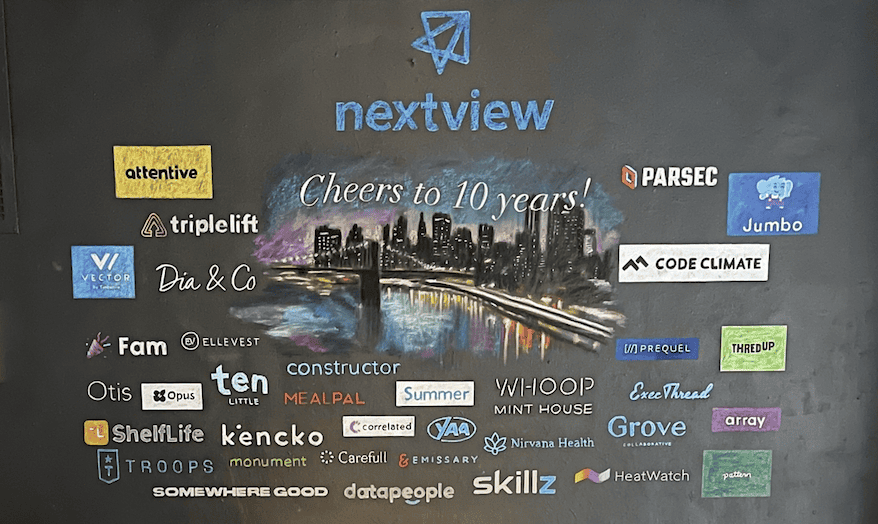

The NextView Ventures Manifesto 2024

We recently launched our new website, just in time for the fall fundraising sprint. This was a huge effort that we’re very proud of, and we owe a lot of thanks to the terrific folks who helped make it happen. One of the joys of this effort was deciding how we wanted to communicate our firm’s essence to the broader world. Believe it or not, we scrutinized every word, which is probably why the site is a bit verbose in spots. To complement this, I wanted to share a manifesto that more fully articulates our convictions and intentions as we conduct our business at NextView. The last time we did this was over six years ago, and while much has changed in the venture landscape, the core DNA of our firm remains the same. This isn’t a detailed play-by-play of our investment model (which you can find on our website), but rather the deeper motivation behind everything we do as a firm.

Purpose

One of the first questions we ask entrepreneurs is “Why?” Why did you decide to devote your talents to this one thing? Why are you willing to face tough odds and great struggle in pursuit of this quest?

Every now and then, entrepreneurs ask us the same question back. It’s surprisingly rare, and I wish it happened more. It’s a worthwhile question! I once asked a Midas List investor what kept him motivated so many years into his venture career (his answer would shock and disappoint you).

Not everyone at NextView would articulate their “why” in the same way. Some of us simply love the spirit of creation – “making something out of nothing,” as one of my partners would say. But embedded in all our answers is a belief in two things.

First, that technology coupled with entrepreneurial creativity is one of the most profound forces available to our society.

Second, that as humans with talents, resources, and capital, we have the agency to direct this force toward worthwhile aims.

These beliefs may seem obvious or trite, but as a society, it seems like we often doubt their truth. There is more skepticism than optimism about technology in many areas of life. People fear the downside risks of algorithms or AI gone awry. There’s a sense of powerlessness among those who long for the way things used to be, or those who truly aren’t in positions of power because of injustice.

As early-stage investors, our purpose is to exercise the agency we have in the narrow domain where we have influence. We aren’t “double-bottom-line” investors, but applying our capital and resources to companies that lead to collective prosperity is much more motivating than the alternative. This is the “why” behind what we do.

Teamwork

My favorite sports team of all time is the San Antonio Spurs. In particular, I think of the Tim Duncan, Manu Ginobili, Tony Parker era from 2001–2015. That team was a model of persistent excellence, exhibiting incredible balance, low drama, great work ethic, and steady leadership. In addition to their remarkable consistency, this team also played the most beautiful brand of basketball I’ve ever seen at their peak. They were both highly reliable AND astonishingly magnificent at their best. This is a model of teamwork and outcomes that inspire us as NextView.

Our firm actually has a very unusual org structure. We’re very top-heavy as early-stage VCs go. We have five equal partners who directly engage with the founders we’re fortunate to partner with. Because of our structure, there’s a persistence of relationships among the partners that allows us to get things done quickly, with conviction, and without drama or infighting. Partnerships are notoriously difficult, and it’s not like we’re in perfect harmony every moment of every day. But there’s a commitment to the greater collective that guides our approach and serves as the most important foundation for the experience that founders have when they interact with NextView.

Non-Consensus

Every early-stage VC in the world claims to be a contrarian and a non-consensus thinker. But very few are. This was even more pronounced during the ZIRP-induced market boom post-COVID. Typically, the only profitable strategy as an early-stage investor is to be non-consensus and right. This means that one’s price of entry is acceptable because not everyone is chasing the same opportunities. The ultimate prize would be a successful and sustainable independent company, but that may only become obvious 10+ years down the line.

However, in a frothy environment, a consensus strategy becomes seemingly profitable in the short term. The focus shifts from independent thinking to simply anticipating what others find attractive and getting access early. It doesn’t matter if the price you pay is high—there’s 10x+ more capital downstream to invest six months later at an elevated valuation. This leads to extraordinary markups and TVPI, which becomes the data that supports more and more larger funds.

This was the world we found ourselves from 2020 to the end of 2022. We had a lot of success in exiting investments during this time, but frankly, struggled with new opportunities. This was a strange period where most early-stage investors were primarily focused on what it would take to get a quick markup rather than investing in a great founder with a unique insight. A generation of early-stage investors learned terrible habits during this period.

The market today is a lot more rational overall, but in some pockets, this thinking continues to persist. As bullish as I am about generative AI, the most worrisome trend is the way non-discerning capital continues to flood into this sector.

We don’t always pull it off, but our goal is to promote non-consensus, independent thought. This is reflected in our decision-making process, where a Partner can make an investment even if all others are skeptical. We actually have a name for consensus opportunities that we know the market will obviously value – we call them “doable deals”. Calling something a “doable deal” ends up being the kiss of death in most investment discussions.

Responsibility

Part of the deal in being a non-consensus lead investor is the responsibility to see this commitment through. This is something we take very seriously, and it leads to some pretty counter-intuitive behavior that is short-term costly but long-term worthwhile.

For example, we are structurally set up to deliver on this responsibility because of our staffing model. Most early-stage investors claim to be high-conviction and hands-on. But can they really deliver on this promise with the team they have assembled?

As one of the most top-heavy seed funds in the business, we make roughly 10–12 new core investments each year, which equates to 1–4 new investments per year per partner. This is highly unusual. Almost all other seed firms make 2-3X more investments per partner, which compromises their ability to deliver on “high-conviction, hands-on investing”. Some folks try to outsource this responsibility through platform teams or junior staff. I would stack our platform offerings against any other seed fund out there, but it is a multiplier of our core offering, not a replacement.

Responsibility also means sticking around, especially when times are tough. This is a tricky balance for investors. Time is our most precious resource, and it’s not the most productive use of time to stay deeply engaged with businesses that are failing to thrive. We’ve seen multiple cases where even the most founder-friendly investors have excused themselves from a company’s board because their time was better spent elsewhere. Other investors just stop paying attention or stop responding to a founder’s emails or phone calls. I can’t imagine anything more disheartening to a founder than this sort of abandonment.

Responsibility also suggests some give and take. As SAFEs have become the norm in pre-seed and seed rounds, there’s an implicit absolution of responsibility among all those involved. Although we also invest in SAFEs, we always institute some board-like cadence of reporting, relationship building, and accountability that mirrors what would occur if and when a board is in place. But honestly, that still results in a different vibe. It makes me think of a line that an old mentor of mine used to say: founders should “treat themselves to shareholders.” There’s wisdom in suggestion.

Innovation

Our entire business is predicated on a thriving innovation economy. Because of this, we have a few strongly held beliefs about how innovation comes about.

First, innovation is broadly distributed. There are benefits of density, but the internet has also unlocked the ability for brilliant minds to thrive in all corners of the globe. Although we are US-focused investors with partners in the major tech hubs of SF, NY, and Boston, our portfolio spans the U.S. and Canada, and we’ve seen companies thrive in a broad range of locations and circumstances.

Second, innovation is highly counterintuitive. I wrote a lengthy post on this recently, but in a nutshell: it disappoints before it surprises. It is characterized by discontinuous leaps, not a predictable progression. And it is prone to constant cycles of disequilibrium, not a steady march toward a steady state.

Third, innovation is not a given. There’s a reason why the United States has thrived in this regard, and we should not take this position for granted. It’s imperative that this country continues to foster an environment where the world’s brightest minds are attracted to this country and can stay and prosper. Markets must continue to function freely without excessive bureaucracy or regulatory overstep. And the right balance needs to be struck so that this remains a place where opportunity is broadly available, while still encouraging and rewarding the bold.

Persistent but Not Dogmatic

NextView is entering its 14th year in existence, making us one of the longest-tenured, continuous partnerships in seed-stage venture. We’ve been doing this a long time, and although things have evolved, we’ve enjoyed a unique persistence of team, strategy, and execution that has served us well. Back to the Spurs, one of their mantras is to “pound the rock” and we certainly take this creed to heart.

That said, one of our core principles for many years has been that we have to be disciplined but not dogmatic. This has led to a culture of experimentation as well as a tolerance for exceptions and outlier decisions. The early-stage venture market is evolving faster than ever, and it’s natural for organizations to become complacent and fail to evolve appropriately. Our hope is that we can always look back every few years and simultaneously say: “Not much has changed” while also saying: “wow, there’s a lot that’s new that wasn’t here before.”

Joy

Howard Lindzon has a blog with the tagline: “Investing for profit and joy.” Honestly, I love that characterization of what we do. Another entrepreneur I know instituted “joy every day” as one of his company’s core values. This is also an amazing mantra for one’s own work and the collective endeavor of a team.

The early-stage market has been really tough over the last few years. That’s why there has been so much turnover in the industry, and I often speak to investors who are worn out or founders who feel exhausted or stuck. But there is also great privilege in the work that we get to do. And beyond that, there is meaning and purpose beyond one’s work. No one is entirely defined by their valuation, exit value, fancy investor, IRR, DPI, or money in the bank. I believe we do our best work when there is joy at the core, and that’s something we hope to instill in our relationships and the relationships forged among the founders in our portfolio collectively.

All of us are hungry to win and passionate about changing things that we see as broken in the status quo. And by definition, having passion means a willingness to suffer hardship along the way. But I genuinely believe that this struggle can be coupled with joy, and we hope to reflect that in the way we pursue our craft.

That’s all for now. Thanks for reading. Let’s build a future worth living in!