Rob Go

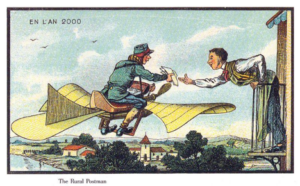

One of my favorite coffee table books is “Future Days: A 19th Century Vision of the Year 2000”. It’s a collection of illustrations commissioned by a French artist in 1899 to try to depict what the world might look like in 100 years. The illustrations are fun, hilarious, and kind of jarring in some ways. Isaac Asimov apparently acquired the pieces and assembled them into book form in 1986. Here’s an example of one of the pieces:

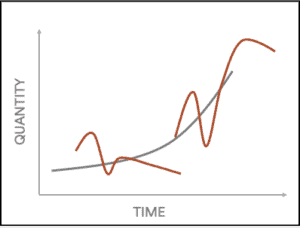

When we look back at innovation cycles of the past, we tend to remember them as smooth, predictable curves. However, when you are actually in the middle of one, innovation feels completely different. This is why our estimations of the future are often so far off and why the opinions of pundits tend to fall all over the map. We are just terrible at predicting how innovation unfolds.

As I’ve reflected on this, I believe that three logical fallacies are what make the future so non-intuitive for most people.

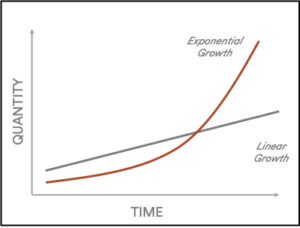

Fallacy 1: Exponential vs. Linear Growth

First, humans intuitively think of things in terms of linear growth. We have a very hard time getting our heads around exponential change. But that’s how innovation unfolds. Things go painfully slow before they go insanely fast. Often, this means that we are terribly disappointed in the short term, but fail in our imaginations in the long term.

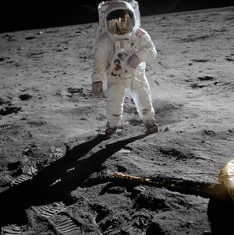

This has been largely discussed and is well understood, so I won’t belabor the point. But a good example of this is how technology evolved from the Wright brothers’ first flight to the point where we were sending rockets into space. It’s kind of crazy that we went from this:

To this in 66 years!

And if you look at what airplanes looked like between these two time periods, you’d think that we were making nearly zero progress for decades. Progress goes very slow before it goes very fast.

Fallacy 2: Monotonic vs. Discontinuous

The second fallacy is that we tend to think that change happens in a continuous, monotonic way. That is, we make steady progress in the same direction over time. But this is often not true. Technological progress usually has many starts and stops. We have multiple boom and bust cycles even within a positive secular trend. And sometimes, the big leaps forward come out of nowhere.

There are two examples to point to here. The first is the mobile internet. I’m old enough to remember when the mobile internet was a major investment theme for VCs back in the early 2000s. We were coming out of the internet bubble, and there was a lot of hope that this would be the next big technology wave. What followed was a period of hope, disappointment, and multiple head fakes. Then Apple and the App Store ushered in a totally new era and mobile innovation exploded. When you zoom out, the overall shape was exponential, but when you zoom in, the path to progress was neither steady nor continuous.

Self-driving cars are another interesting example. If you look at two points in time, you could draw a pretty steady curve of progress. But in reality, we had many fits and starts. Shortly after the Cruise acquisition by GM, we saw countless articles about how self-driving cars were going to reshape society and how investors were betting on the second-order effects of this change. Then, a few years later, the same folks wrote about why the last mile of self-driving cars might actually be impossible, and there was broad skepticism that this would ever come to fruition. But we are back to a moment of optimism again, and Tesla’s new FSD12 software seems to be a discontinuous leap in capability based on a completely different, non-rules based software framework. Progress in this field has not been monotonic.

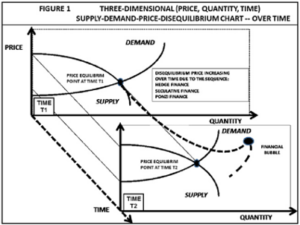

Fallacy 3: Growth Markets Tend Towards Disequilibrium, Not Equilibrium

The third fallacy is that we tend to look for equilibrium in the economy. That’s one of the first things we learn in first-year economics, and it’s strangely soothing to think that market forces cause supply and demand to meet. Actually, supply and demand do tend to meet in the economy, but the fallacy comes from the belief that this equilibrium tends to remain stable. But it does not.

The actual reality is that growth markets are chaotic by nature and are almost always in disequilibrium. This is because greed and fear are rampant, which constantly drive the curves to oscillate between boom and bust cycles. This is particularly true in the most attractive segments of the world economy when interest rates are low because capital tries to flow into the highest returning areas and is willing to bear significant risk to chase returns. This is probably amplified by the lack of transparency in private companies and the challenge of determining true market prices.

This is why, in every year of my career, investors have generally felt like the market was either crazy or that the sky was falling. You almost never felt like we were in a state of equilibrium. Some investors would constantly lament periods of seeming excess, only to miss out on one of the greatest bull markets of my lifetime. After hearing the same laments over and over for the last 15 years, I believe that the actual lesson is that those who participate in the innovation economy should not wait around for equilibrium, but should be comfortable in constant disequilibrium. As I’ve written elsewhere, markets are like a pendulum; they are at equilibrium for just a split second, and tend to be moving the fastest when approaching or exiting that point.

And so, when I think about this current wave of AI innovation, I think it’s helpful to keep these three fallacies at the forefront of your mind. We should expect things to move more slowly than we think for a long time, and then much more quickly than we imagined in the longer term. We should expect there to be booms and busts and head fakes along the way, and then some discontinuous leaps of progress that might come out of nowhere (OpenAI thankfully gave us one of these discontinuous leaps fairly recently). And we should expect this market to be chaotic and filled with speculation and inefficiencies. Disequilibrium abounds.

Even if we internalize all this, it’s going to be very hard to resist the urge to fall back into the more comfortable mental models that we are all used to. But I guess that’s what makes the journey unpredictable, but hopefully quite amazing.

Don’t panic; enjoy the ride.