10 Reflections After 10 Years of NextView

A few weeks ago, we hosted a small dinner for a number of portfolio company founders, LP’s, and friends of the firm. We’ll probably do a few of these over the next few months as we make our way back around the country and folks get more comfortable meeting in larger groups in person.

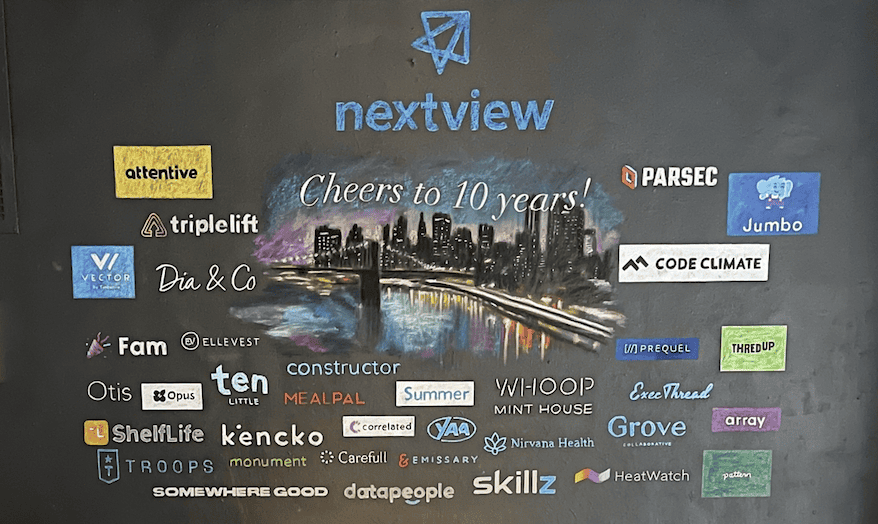

Part of the reason to do this was just to reconnect after a long time apart. But another was that this year marks NextView’s 10th year in existence.

These first ten years have been pretty special personally. It’s by far the longest time I’ve spent working on any one thing, and I feel very blessed to have been able to work with my partners, colleagues, founders, and collaborators. I’m also grateful for the adventure and the learnings that we’ve been able to accumulate over the last decade. This is a big milestone for us, but really, it’s just the beginning of what will hopefully be a multi-decade endeavor for me individually, and perhaps a multi-generational endeavor for the firm. But before we look too quickly towards the future, I thought I’d look back for a moment and share ten thoughts and reflections from our first decade as a firm.

1. Change will always happen, should never be unexpected, and should be embraced

When I started in venture, I naively believed that it was an industry that was unlikely to change dramatically over the years. I had learned a number of hard and fast rules from those who had practiced the craft for decades before, and I figured that although we invest in change, our business itself is likely to be quite stable.

Boy was I wrong. In the last ten years, the industry has changed dramatically. $1M large seeds rounds now look more like $5M rounds or much more. We’ve seen mega funds and platforms, a huge surge in late stage funds, crowdfunding, rolling funds, and everything in between. New funds have formed, old market leaders are gone or walking dead. The only thing that seems to be the same is that Sequoia is still the best.

Amidst all this, it’s easy to be a skeptic and grumble about how things are changing for the worse. But the reality is that the more interesting the market, the more likely there is to be rapid and unpredictable change. It’s a gift to be in a market with massive change, so embrace it. Embracing change was something that was easier for me to do when I was 30 and just getting started with NextView. But it’s getting harder and harder as I advance in this career, and I really need to keep reminding myself that it’s still day one.

2. Patience is a virtue

My partners will tell you that I am an incredibly impatient person. My favorite saying internally is “anything worth doing is worth doing fast”. I like action, motion, and I get frustrated when I feel things stalling or going sideways.

But one thing I’ve really learned in our first ten years is that most great things take time to blossom. Time is hard to hack. You always want to do more faster, but some things just need to play out over months or years (or more).

One industry specific example is the strange fascination among some LPs and GPs around term IRR. This is the implied rate of return of a fund based on the value (mostly unrealized) of a portfolio. Even though everyone knows that VC funds take 10+ years to come to fruition, one often can’t help but benchmark themselves based on IRR in the early days. Early on, I sweated the fact that our early funds had pretty “meh” IRR in the first 3-5 years. But today, these same funds are looking excellent on both a TVPI and more importantly, a DPI basis. This may not always happen, but it’s been reassuring to see that this really is a long-term business.

3. There is a Goldilocks zone between too much dogma and lack of discipline

One of our core beliefs at NextView is to be disciplined but not dogmatic. That was NOT one of our core beliefs when we started. And I think that it might end up being one of the most important beliefs that sustains our firm over time.

Having a lack of discipline can kill a venture firm and venture investor. You can’t just start chasing the shiny new thing every moment something new arises. You’ll never have the staying power to commit when things get tough or to get really good and build real differentiation if you just keep jumping to the next new thing. You’ll also be a bit of a nightmare to work with because you’ll seem totally erratic, unpredictable, and without real conviction.

But being too dogmatic is probably more deadly for a venture firm. It will cause you to persist too long on the wrong strategy if the market or situation changes. It may cause you to risk irrelevancy and to restrict the creativity of your ideas. Also, VC is by nature an outlier business. That sort of investing doesn’t lend itself to very strict rules and parameters. You need to find ways to allow for unexpected good things to happen.

One example of this was the accelerator that we launched in the early innings of the pandemic. In a way, it was totally undisciplined, because it was a totally new program in the midst of a wildly uncertain time. We also had just raised our largest fund to date, so why are we “wasting” our time with $200K checks into concept stage companies? But the experiment is looking to be a success. We executed it with discipline, but were open about how we would approach it. There are companies that are thriving in this batch that we may not have invested in if we had been too dogmatic. Also, being too dogmatic isn’t very fun J

4. What matters is effective post-money at exit

Seed funds (and their LPs) are very fixated on ownership at entry. 90% of the airtime around ownership and valuations is focused on what happens when the first check is written. We think about this a lot too.

But if you start talking about “effective post money”, folks will either stare at you blankly or try to move on quickly. Why is this? Because it’s a lot more fun for a seed investor to talk about how they invested in a unicorn at a $8M pre than to have that same person say that their effective post-money is actually $100M.

How can this happen? Effective post money is the effective valuation of an investor’s dollars at any one time. For example, a fund might invest $500K out of a $2M round at a $10M post money as their first check. But over time, that fund may invest another $2M in later rounds. If the company wasn’t that capital efficient, the fund may end up owning 2.5% at exit due to dilution. In this case, the effective post-money is $2.5M / 2.5% = $100M. So it’s like this same fund actually invested $2.5M in a mid stage round at a $100M post. All $500K checks at a $10M post are not created equal.

Practically speaking, this suggests that raising big rounds isn’t always a great thing. It creates dilution, and investing in these rounds increases your effective post-money. It may still work out great, but it forces a bit more nuance in investing and follow-on decisions.

5. Traction creates opportunity

The phrase I say most often internally is that “traction creates opportunity”. This means a number of different things. But the general idea is that for software driven businesses, traction can create unpredictable upside that is hard to account for but should not be ignored.

This comes up most often when we talk about market size. I think the biggest miss for most VC’s occur when they pass on an exceptional team and opportunity because they underestimate the potential of a company’s market. In some cases, great companies massively expand the definition or potential of the market with innovative products, technology leverage, and great execution. This obviously doesn’t happen all the time, but it does happen sometimes, and when it does, it often yields the biggest companies on the planet.

6. Define markets properly

Related to #5, sometimes investors miss out on market potential because they just incorrectly define a company’s market opportunity. Looking back, our biggest mistakes and omissions as a firm can often be traced to improper market definition. DraftKings was the classic example of this. One mistake we made was defining the market as “of all the people who play fantasy sports, how many would want to play for money”. This definition yielded a pretty small opportunity.

Turns out the right way to think about it was “how many people like to play games for money? And how many of those people like sports?”. That approach yields a huge market. Today, DraftKings is a $20B market cap company.

7. Founders and investors should make each other a little uncomfortable

This one is controversial. It’s easy as an investor or founder to have a natural affinity for someone that you feel more or less at ease with. But as I’ve done this for a while, my POV is that it’s often better when founders and investors make each other feel uncomfortable in some way.

One reason is that it makes sure that you are not working with someone just like you. There are many different styles, personality traits, and beliefs that make up different people. And most high performing people are a little quirky or extreme in some way. If someone doesn’t make you a little uncomfortable, that might be a signal that you are solving too much for someone that is too similar to you. That may not seem like a huge problem, but it means that you are artificially limiting your pool of potential founders or investors that you work with. It’s part of what I think has held our industry back for a long time in terms of the diversity of founders we’ve backed and the creativity of the ideas we have pursued.

From an investor’s perspective, another thing I’ve noticed is that the best founders make me feel a little off balance and on the defensive. Sometimes, it’s their sheer intensity and focus that makes me feel uncomfortable. I realize that I need to be mentally prepared to engage with this founder at a high level, and can’t just relax and mail it in. Sometimes, it’s that the founder seems a little out of control, and I worry that they will break things. But ideally, you want to work with founders that push the envelope, and make you feel like you need to try to put shock absorbers around them so that he or she doesn’t go overboard. That’s a heck of a lot better than founders that do everything by the book or don’t push the envelope (or worse, don’t do things that you don’t agree with). This is why I am allergic to the talk about trying to work with founders that are “coachable”. I think the best founders do listen to feedback, but probably disregard my advice more than I’d like (and end up being right).

From a founder’s perspective, it’s easy to optimize for investors or board members that you are very comfortable with. For example, folks that you feel like will be perpetual cheerleaders or who seem to be agreeable to everything to are doing. But this has two pitfalls. First, you won’t get the most out of this sort of investor. You want someone who will challenge you and be an intellectual sparring partner. If someone is too nice and agreeable, you may feel like you are sparring, but you are really just shadowboxing and will be in for a surprise when you get a real punch in the face. Second, investors always put on their very best behavior when they are trying to sell their way into a deal. So an investor that may seem like the greatest and most collaborative person may end up being a nightmare when the going gets tough. This is why I always encourage founders to focus almost entirely on the feedback they hear from other founders vs. just their gut feelings and impressions during the fundraise process. To use a dating analogy – you don’t really care if an investor is super great to date. You want to figure out how they are when you are actually married. And you have the luxury to be able to talk to a bunch of folks who have been or are currently married to them, so pay attention to what these current and past spouses have to say!

8. Competition matters… or does it?

This is something I’m still struggling with honestly, so maybe this reflection is a cop-out. It’s hard to believe, but after 12+ years in VC, I am still not sure how much competition matters. It’s conventional wisdom to say that it doesn’t, and that startups should keep their head down and execute. And to some degree, I believe that, especially when you are talking about bigger, slow moving incumbents.

But I think the generic advice that competition doesn’t matter isn’t true. Competition matters when it comes to talent, customers, funders, partners, attention, and others. Also, some markets are such that competitors might blow their respective brains out by going too aggressively head-to-head.

One of my side-project ideas is to try to create a new strategy course at a business school focused on startup competition. It would be case based, and each case would be an A vs. B matchup. For example, Blue Apron vs. HelloFresh, Doordash vs. Uber Eats, Amplitude vs. Mixpanel, maybe something in the POS space like Square vs. Toast, etc. It would be super fun. I would enjoy trying to create this, and I’d really enjoy taking the course if it exists (please let me know if it already exists somewhere).

9. Fundraising is unpredictable. Don’t let it get you down.

If I had to distill all my fundraising advice down to two things, it’s these two. First, fundraising is unpredictable. I’m constantly surprised by how a fundraise process goes, who digs in or not, and how terms ultimately come together. The takeaway for me is to have a broad process and don’t try to be too clever around sequencing meetings or staggering your prospect list. This is true for companies that we work with and advise on their fundraising process, and it’s true in our own fundraising as well. I can tell a story looking backwards why our LP base was carefully constructed. But in a lot of ways, the things that made magic happen between ourselves and our LPs was driven by timing, luck, chemistry, and other factors that were hard to predict at the time. We deeply value these relationships, but they were not all perfectly planned.

The second is this – don’t let fundraising get you down. As my partner Lee always says, fundraising isn’t about convincing skeptics, it’s a search for true believers. I was speaking to the former CFO of one of our most valuable portfolio companies the other day, and she recounted how this company once pitched 70 investors to barely get a term sheet. It’s brutal to be in that position as a founder, and for everyone that has a happy ending like this, there are many others where a similar experience might end up being the end of the road.

Which leads me to my bigger point on this. Being a founder and fundraising can be a massive assault on your ego and self-worth. Founders understandably might closely intermingle their personal sense of identity with the value and success of their companies. I’ve done this and struggle with this constantly as a GP and founder of an investment fund.

I think the most useful thing to do as a founder is to pause for a moment and reset your perspective. While the pursuit of your company may be world changing, significant, and noble, it isn’t an ultimate thing. I think doing this can free some folks to make better decisions and perform better without allowing the pressure to get toxic for one’s own health and relationships. And while you are working through this, know that you are not alone. Talk to someone, get a coach or find a peer group. You may be surprised to know that many many founders and investors have gone through a very similar experience and can share words of encouragement and practical help.

10. It pays to be optimistic

Most would be surprised to hear that I’m sort of a pessimist by nature. I’m constantly paranoid that things will fall apart or that markets or companies are running too hot. I’m also quick to pick apart what might be wrong or misguided about an emerging new trend or hot sector.

We are currently in an incredible economic bull market overall, and perhaps a once-in-a-lifetime revolution in tech. Perhaps we are nearing the end and in for a world of hurt in the coming years. But then again, this is what skeptics have been predicting for 10+ years.

I remember when I first started NextView and I was giving a talk to an audience in Boston about innovative new consumer businesses and internet business models. Some folks in the audience jeered because I was young, inexperienced, and hadn’t been an investor when the internet bubble burst. What I was purporting was just “the greater fool theory”. This was in 2011, and I still remember that warning. I’m glad I didn’t listen.

I have been on the other side of this argument when it came to crypto and some other mega trends as well. My realization is that part of the negative bias comes from pedigree and success. When one has achieved some success, there is greater risk in jumping on a new bandwagon, getting it wrong, and looking dumb. The cost of being incorrect becomes magnified as one has more than just capital to lose.

But in a world of power-law distributions and the near magical scale enabled by software, the potential upside far outweighs the downside in most cases. It’s important to put one’s ego and desire for self preservation aside and choose to peel off your mental callouses and be optimistic. You may get massive egg on your face, but you also create the potential for spectacular outcomes. It’s a much more enjoyable way to live and invest as well.

Well, that’s it. There are probably another 10 reflections that I wish I could include into this already long post. The good news is that I’m only 41, so hopefully I’ll get the chance to write a couple more of these posts in the decades ahead. Until then, thanks for reading and following along with our story. It’s been my deepest professional joy to work with the founders we’ve invested in and with my partners and colleagues at NextView.