How is the VC Asset Class Doing?

One of my more popular posts in recent years was a long write-up on how VC’s get measured. It occurred to me that about 2 years has transpired since that original post and I thought I’d write a follow-up. At the time, I spent most of my time describing the metrics themselves and how VCs and their LPs evaluate performance based on these measurements. This time, I’ll spend a bit more time thinking through the benchmarks to get a sense for how the VC business is doing.

If you aren’t familiar with these metrics, I recommend reading the original post to get a sense of the numbers that I’ll be reviewing here. If you really like geeking out on this sort of thing, there are a bunch of places to learn more, but I’d start at OpenLP, which is a great collection of writing on these topics brought together by Beezer Clarkson and our friends at Sapphire Ventures.

So, without further ado, let’s look at how the VC asset class is doing, starting with funds that are more mature.

How Have the Last Two Years Treated Older Vintages?

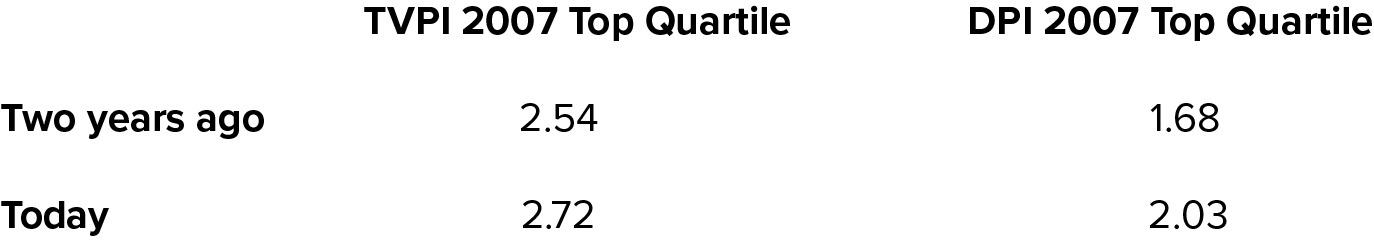

One of the things I pointed out in my prior post was that even though the 2007 vintage was 10 years old, the vast majority of the value was still unrealized. At the time, the upper quartile TVPI was 2.54 and DPI was 1.68. This means that on an unrealized basis, this vintage looked ok, but the actual realized returns were very mediocre. There was nearly a 1X gap between realized and unrealized for the top quartile fund.

If we compare the 2007 vintage data today vs. what we looked at 2 years ago, it gives us a sense of how much liquidity that vintage has enjoyed in the last couple years.

Here is the data in a nutshell

In summary, it looks like the 2007 vintage hasn’t seen that much additional appreciation in the last couple years. Top quartile TVPI went up a little, from 2.54-2.72. If you look at the median TVPI, it’s basically unchanged over this period.

DPI looks a bit better. The top quartile has distributed 2.03x (vs. 1.68) and the median fund now has distributed 1.27X (vs. 1.04 2 years ago). However, this is what you would expect later in the life of the fund. Typically, one or two of the companies in a fund may continue to appreciate, but most of a VC’s portfolio has probably been realized, written off, or has maxed out its value. VCs would be looking to get liquidity for their companies to generate DPI if possible. The longer the portfolio maintains the same value without distributing back cash, the worse the fund’s ultimate IRR.

So, is this good or bad? 12 years into a fund, I think LPs are probably primarily thinking about DPI. Based on that metric, the top quartile fund has now distributed 2.03X after 12 years. This equates to something in the neighborhood of a 10% IRR, which isn’t great given the illiquidity of the asset class and strength of the public markets. This also means that 75% of the funds of this vintage did worse. Ouch.

How Have the More Recent Vintages Performed?

The story for the more recent vintages is somewhat brighter. If you look 5 years later at the 2012 vintage, top quartile TVPI is 2.29. That’s only 0.5X worse than the vintage that is 5 years older. In fact, the top quartile TVPI of the 2011 vintage is 2.6, nearly the same as 2007.

The top quartile DPI for the 2012 vintage is 0.62. So, that means that the top quartile fund has distributed 62% of paid-in capital after 7 years. Is this good or bad?

One way to think about this is how quickly LPs expect to get their capital back from a VC commitment. Typically, when an LP makes a commitment to a new VC relationship, they are expecting to stay with that group for at least 2-3 funds. This is because the feedback cycle in venture is long, and VCs favor LPs with a long-term perspective.

I’ve heard one LP heuristic that the capital returned from the first commitment to a new fund should pay for the investment in the fourth fund by the time that comes around.

Given that most VCs these days seem to be raising new funds every 2 years (and sometimes faster), this equates to an expectation of a 1X DPI by year 6 or 7. Clearly, 0.62 is quite a bit less than that. So, an LP in this fund would probably have to make a decision on whether or not to keep investing with the firm before they have the principal back from their original investment.

Another way to think about this is how 0.62 DPI for a 7-year old fund compares to prior time periods. When we looked at the data two years ago, the vintage that was 7 years old had a top quartile with 0.84 DPI. So, compared to the 0.62 DPI of the current 7-year old vintage, this is quite a bit better. It’s also meaningfully closer to the 1X DPI threshold referenced above.

So, in a nutshell, this suggests that the 2012 vintage is appreciating in value faster than the older vintages but seem to be distributing out cash more slowly. This isn’t a super scientific analysis, but it does seem to be consistent with what I’ve seen anecdotally. Over the last 10 years, we’ve been in a bull market with considerable froth in late stage financing activity and valuations. This would suggest that TVPI would be performing well. At the same time, despite some realizations in recent years through M&A, PE acquisitions, and IPOs, the general sense I get from LPs is that the level of distributions don’t quite line up with the unrealized performance. This data seems to line up with the narrative I’m hearing on the ground.

LP Constraints

The trends described above in VC performance have an upstream effect on Limited Partners which is somewhat counter-intuitive. Most LPs are trying to manage some targeted asset allocation. This means LPs want to make sure that any one asset class makes up some targeted % of the assets overall. For example, a $10B endowment might be looking to have 10% ($1B) allocated to venture capital at any one time.

So, if the venture asset class performs well in terms of unrealized mark-ups, the % of VC relative to the total portfolio actually increases. That 10% might start to look more like 12% or 15%. Ironically, this means that the LPs may feel like they have too much venture capital, even if they are super excited about their portfolio.

The way this gets resolved is if their VC portfolio becomes liquid. If assets from venture capital get distributed, this means that what was VC is now cash, lowering the % of the portfolio that is allocated to that asset. This allows the LP to deploy more cash into whatever asset class they want. And over time, if VC is performing well, the LP may actively manage up their allocation to venture.

However, as described above, the pace of distributions (DPI) has been lagging the total appreciation in VC portfolios (TVPI). This puts pressure on the asset allocation models for LPs, who either have to accept an increased % allocated to venture, or pull back on venture commitments despite the fact that the asset class seems to be performing well.

This is made more difficult because most VCs have increased their pace of fundraising over the last 5-10 years. So, as described above, VC’s are asking for more capital sooner than before, and also distributing capital back more slowly than before, putting more strain on these allocation models.

How Good is Good?

Despite this strain, LPs are still trying to find opportunities to make commitments to new VC relationships. LPs are very selective about this, but those that have a long-term commitment to venture are always on the lookout for teams that might produce true outlier funds.

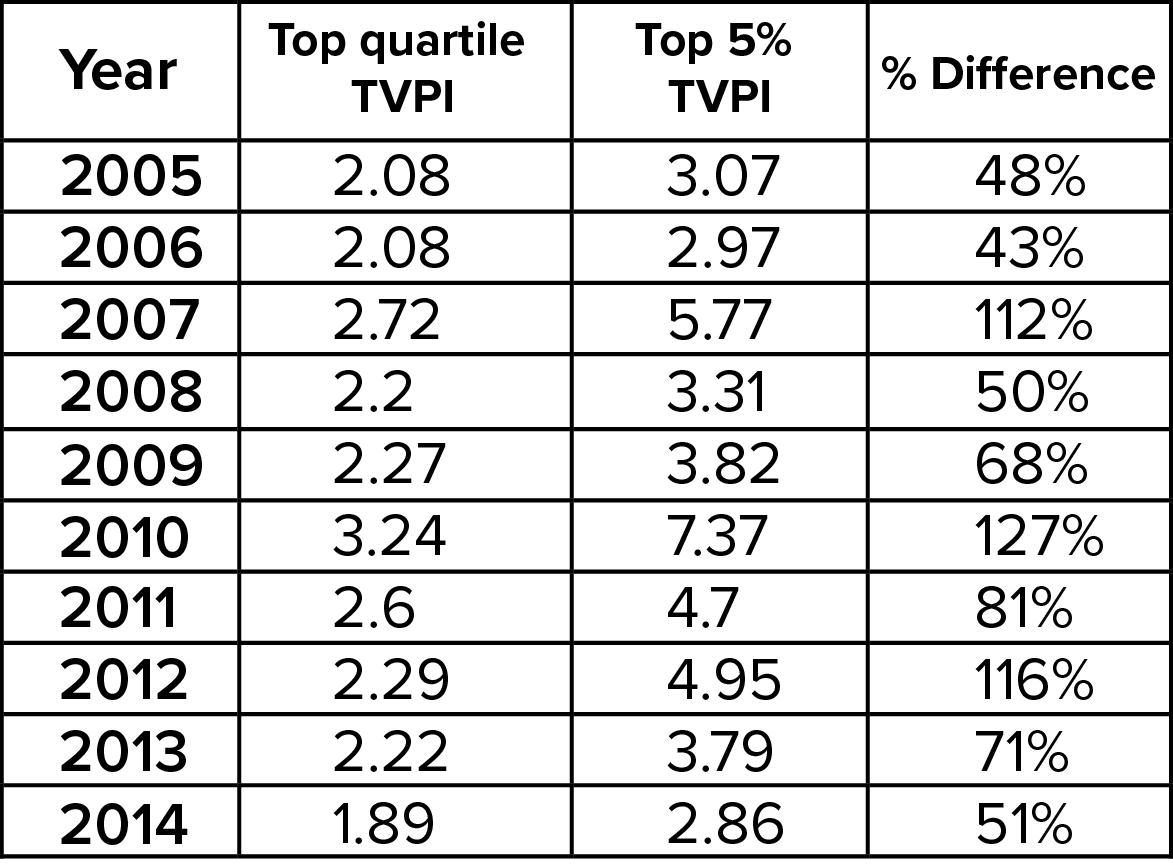

So, how good is an outlier fund? So far in this post, I’ve honed in mostly on the top-quartile threshold, which masks the power-law that is exhibited in both startups and the VC industry. Outside of the mid 1990 vintages, upper quartile benchmarks aren’t actually that exciting. But the very best funds (Cambridge reports the top 5%) perform much better.

For the 2012 vintage, the top 5% fund had a TVPI of 4.49. For 2007, it was 5.77. Both very good performance. By the way, the top 5% threshold probably represents the 3rd or 4th best fund of its vintage, since there are 40-80 funds per year in this dataset. I’d bet the very best 1-2 funds probably perform meaningfully better than this threshold.

What I find interesting is that there is a lot of variation in the gap between the top 5% and the top quartile benchmarks.

Looking at all vintages from 2005 to 2014, the top 5% TVPI is between 40% to 127% better than the top quartile TVPI. The biggest delta was in 2010, and guess what company raised their first outside funding round that year – Uber.

While top quartile performance tends to be solid for many vintages, the aspiration of the most sophisticated VC LPs is to invest with funds that generate outlier performance, which could be a 5X or better. So the way these LPs evaluate venture commitments is skewed towards trying to find those outliers.

Some LPs take a bit of a rear-view mirror approach and try to find VCs that have had these blockbuster funds before, and then back them going forward. But it’s not often the case that VCs will produce these sorts of returns consistently, especially as markets change and as fund sizes tend of increase significantly after blockbuster success.

Instead, some other LPs try to keep their eyes open for managers that seem to have the right combination of strategy, hunger, portfolio construction, and sourcing advantage that might result in a blockbuster fund in the future.

These may look like first time managers with a unique approach, high potential GPs that are spinning out of larger funds, or firms have been around for a few funds that are gaining momentum and seem primed for a breakout.

The Hundred Billion Dollar Question

I think the Hundred Billion Dollar question for LPs and VCs is how the current class of VC funds are going to perform when all is said and done. Those who are bearish will say that many funds will ultimately perform more poorly than where they are valued today, as their most valuable companies are being propped up by late stage investors that have mis-priced these assets. The cases of WeWork and Uber cast a cloud of doubt over funds that are largely driven by one or two outlier companies that may have a tremendous valuation, but shaky underlying business metrics.

On top of this, the uncertainty about where we are in the economic cycle casts further doubt about the ultimate performance of these funds. In looking at the data, it’s interesting to note that the TVPI for funds from 2002-2006 is pretty weak. Although there are many factors at work, one challenge of those vintages is that most of those portfolios more or less came of age when the 2008 economic crisis occurred. If a similar large-scale slowdown occurs in the market in the next year or two, you’ll likely see plummeting performance of funds that are relatively far long but haven’t generated significant liquidity.

The bull case is that apart from a relatively small number of companies, the best startup companies are real businesses with significant potential for continued growth and eventual profitability. The level of innovation across all sectors is at perhaps an unprecedented level of volume and quality, and the human capital that is flocking to tech startups is the best we’ve ever seen. Even if there is an economic crisis, there is substantial late stage capital in the market to be able to support many of the strong companies. These growth rounds may be more dilutive than planned, but will still occur without punitive terms and allow founders, teams, and early investors to emerge with very successful outcomes at the very end.