The Due Diligence Hierarchy of Pain

When a founder is raising money, he/she should expect that any serious investor will conduct some level of due diligence before getting to yes. This could look somewhat different depending on the maturity of the business. Seed stage companies will mostly face questions around the team and market. More mature companies will have to answer more detailed questions around their tech, product, and business.

Due diligence may seem like a drag, but partnering with an investor is a serious commitment, and you want to make sure that whoever you work with has built real conviction about you and your company. Also, investors are not experts in your business, so asking dumb questions here or there or creating some level of yield loss may be unavoidable.

But there is obviously a cost associated with each step of diligence, and this cost is multiplied across all the investors that are doing real work. There is also social capital at stake in certain parts of the process that creates real cost as well

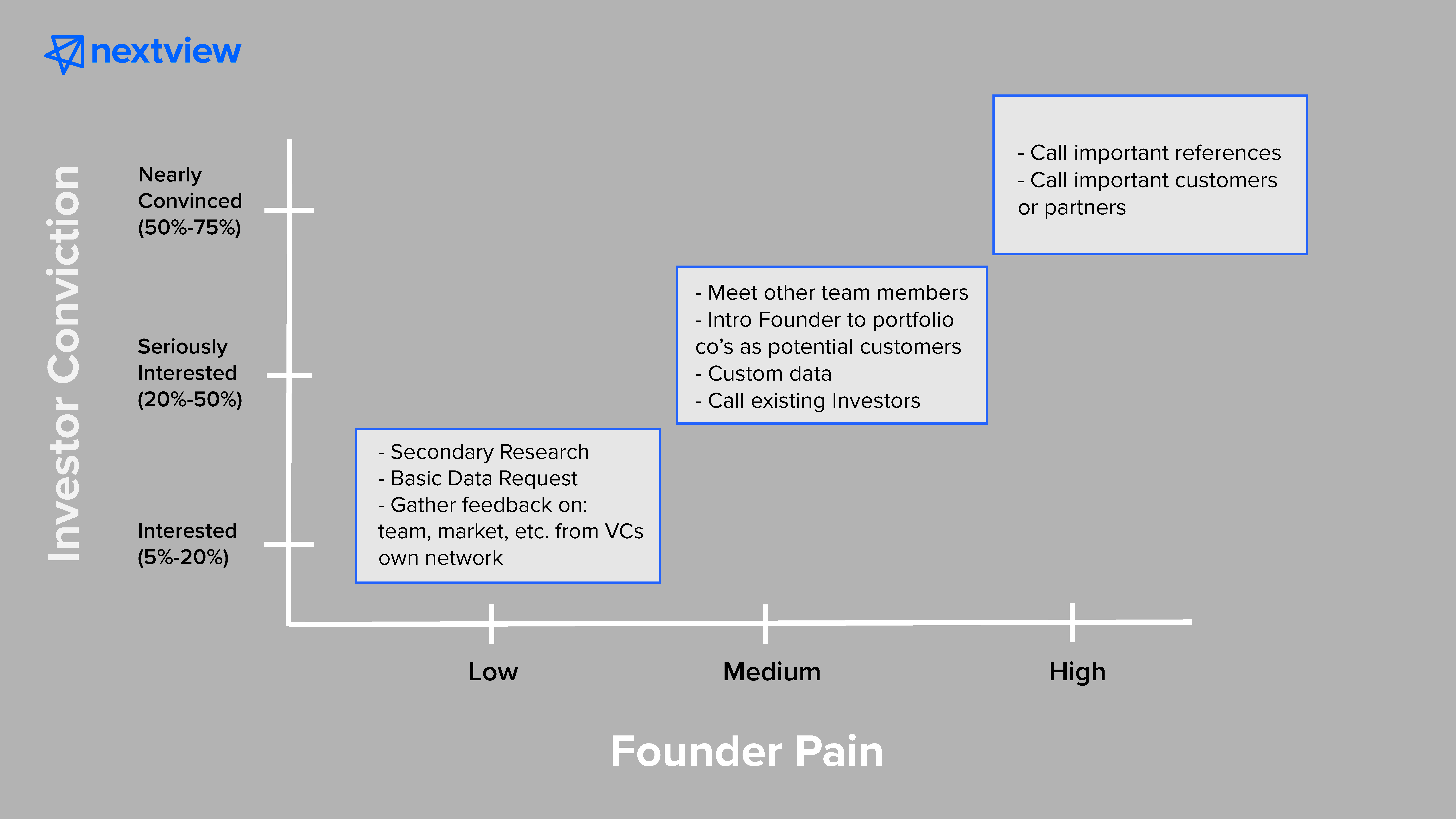

I find that most investors I like to work with are pretty mindful of the cost associated with each step of their due diligence. They tend to have some sort of framework in their mind with a hierarchy of conviction and hierarchy of pain they are willing to put founders through. For me, it looks something like this:

The first layer of diligence happens when an investor is early in their process, but intrigued. They have probably done one or two meetings and some cursory internet research but are only 5-20% likely to actually invest. The types of diligence they should be doing are hopefully relatively costless to the founder. In includes things like:

- Review third party research or ask for data sources or reports referenced in your pitch

- Reach out to people that they know well for quick feedback on you or your team

- Reach out to founders or execs that they are close to that might have a POV on your product or business

- Review business data that companies at your stage should have available or should be easy to produce. There is obviously going to be some disagreement here about what appropriate expectations are. But in a way, seeing what an investor asks for gives you a sense of how they approach the stage of the business you are in. Conversely the VC is able to benchmark the maturity of your data and analytics function against other similarly staged companies as well.

The second layer of diligence occurs when an investor is starting to get seriously interested. Only at this point do they start to do things that should incur real cost to the company. They are still less than 50% likely to actually make an investment, and are probably closer to 20-25%. This includes things like:

- Making intros to portfolio companies that are potential customers. In a way, customer intros are always good, so this could also be done earlier in the process. But I think this does have some cost because a founder would prioritize these potential customers in the interest of moving their fundraising timeline, and that re-jiggering of priorities may be unnatural and has real cost

- Asking for bespoke data that would require additional work to pull together

- Having conversations with your existing investors

- Meeting with other members of your team. This is something that I think may seem costless to investors but I think is pretty disruptive. CEO’s ought to try to shield their team from the time and emotional roller-coaster of fundraising, and speaking to lots of investors that don’t ultimately get there is pretty de-motivating to a team member. Thoughtful investors should know this and be respectful of that cost.

There are certain diligence items that are pretty costly to a founder and should only be done if an investor feels like they are nearly there. Hopefully, it also means that they have buy-in from their colleagues in addition to having built reasonable conviction themselves. There is no way an investor can realistically be better than 75% of the way there before doing this kind of work, but hopefully they are pretty close.

- Calling on-list references, or asking for intros to very senior people that you have a relationship with. These are people who would vouch for you, but you only want to lean on for a small handful of high priority investors.

- Talking to your customers. If you are an early stage company, this is particularly sensitive, so good investors tend to do this late in a process. But you should still try to prepare one or two customers that are friendly and would be willing to take 2-3 reference calls on your behalf as part of your fundraise. If you are a business that is much further along, speaking to customers is probably less costly and can be done earlier in the process. There is almost nothing more helpful than speaking to customers, and if you have thousands of them, it’s probably easy enough for an investor to reach out to someone they already know or chat with a customer or two for 15-20 minutes.

A couple thoughts come out of this.

First, it is a real red flag if an investor deviates from this sort of logical progression. It’s also a red flag if an investor asks for something on the upper right segment of the chart without some acknowledgement of the cost. Of course, investors can’t promise that they’ll get to yes without doing work, but most are pretty respectful. It’s also fair for a founder to ask an investor how far they are in their process, or to ask to hold off on something sensitive until they are further along This can backfire if it seems to suggest weakness or a lack of transparency, but it’s the right thing to do if an investor is asking for something unreasonable too soon.

Second, founders should prioritize their efforts with funds that have a history of leading rounds. Some investors I notice will keep doing due diligence endlessly to “hang around the hoop” but are really slow playing it because they don’t feel comfortable leading. My recommendation is to try to quickly decipher the percent of the time a fund leads the kind of round you are raising. If it’s 50% or more, I’d prioritize their requests. If it’s less than 50%, I’d be reluctant to offer anything in the upper right segment of the chart, and I’d be sensitive to any red flags discussed above.

Third, I find that different investors have different approaches to investigating competition. I tend to be very customer centric, and try to get customers to tell me about the pros and cons of the competition. Some firms will try to call all the competitors and see if they are raising and try to hear their pitch. I think this is kind of fair game, since it’s the job of the investor to try to invest in the best company. But it sucks if you are the one being called and you feel like the only reason an investor is talking to you is because they are considering an investment in a competitor. It also sucks if the investor passes along your data to competitors, which should be a total no-no but does happen.

Fourth, in the course of this process, you should start doing your own due diligence on your prospective investors. Typically, founders ask for investor references after a term sheet as been presented or there has been some clear approval from their team to move forward with the investment. But along the way, you should also be talking to folks in your network that have experience with the particular investor and firm. This is probably fodder for another post.

Finally, you can actually use the due diligence process to your advantage in building momentum for your round. You are in control of the information flow, so you can time the process such that funds hopefully get serious at around the same time to create a competitive dynamic. You can also use the dialog around due diligence as a way to really test the seriousness of an investor. I am not a fan of preparing a full data room and then just giving prospective investors full access.

It takes work on the investor’s part to digest your information and then ask for specific follow-ups, so making them go through that step actually can help to qualify them. Responding too quickly with too much data may seem helpful, but sacrifices the opportunity to keep the ball rolling with ongoing engagement. One of my favorite posts on this topic is from Mark Suster: “Remind me why I love you again”. Working through an investor’s due diligence process can feel like a grind, but it can actually be used strategically to drive the right kind of outcome for your round.