A Crisis Moment for Seed VC

Seed funds are facing an existential crisis. This has been frequently discussed behind closed doors, and more and more of this discussion is spilling out publicly among more experienced managers and LPs. Some dismiss this as a cyclical issue that is bound to recover, while others (like me) think that it’s more of a permanent shift.

This is a long read, but I’ll highlight four interrelated factors that are creating this existential threat to seed:

- Industry maturation

- The two unstoppable forces

- Power law as consensus

- The AI platform shift

Buckle up, let’s go.

Industry Maturation

This has been discussed before, so I won’t spend too long on this topic. All industries go through some form of maturation from a cottage industry into one that eventually favors scale. When we started NextView in 2011, we used the metaphor of the beer industry to describe the inevitable evolution of the VC business. What began as a cottage industry with many different firms eventually became a barbell. On one end of the spectrum, you have mega firms that compete on scale and scope. In VC, you have A16Z, General Catalyst, Sequoia, and others. These are the Anheuser-Busch’s of the venture world that compete across stages, markets, geographies, and product types.

On the other end of the spectrum is the rise of craft players. These are the craft brewers that produce artisanal, specialized products. The venture corollary is the rise of seed VCs in the 2008 – 2015 time period. For a period, these new players thrived as the market was desperate for an alternative to the mega-funds that were so large that they couldn’t focus on the needs of much earlier-stage companies. The middle part of the venture market was subsequently hollowed out, resulting in a more barbell-like industry structure.

But what happened in the beer industry has been mirrored in the venture business. There was a proliferation of craft brewers that elevated the quality of the product, but eroded the rents available for the small producer. There still remain a few elite craft brewers that extract disproportionate profits. But let’s be honest, there are many, many craft brewers, and most products are “good enough.” The same can be said for seed-focused VC funds.

Meanwhile, both mega-brewers and mega-VC funds have improved their offerings, and although craft players still exist in large numbers, the excess profits of this segment have been eroded to the point that most of these firms are not thriving.

I think the beer market presents some clues as to how seed players might still find a way to thrive, but I’ll save that for the next post. For now, let’s move on to topic number two.

Two Unstoppable Forces

As the VC industry has matured, two significant forces have emerged that have created massive problems for seed investors. Whether they admit it or not, seed managers are stuck between a rock and a hard place with two forces that are eating a huge percent of the market, leaving them to play along the edges.

Force number one is Y Combinator (and, to a lesser extent, 3-5 other similar programs). Seed investors love to bash YC, but I’d argue that it is by far the most impressive institution in early-stage investing. First, YC has insane scale. They target about 125 companies per batch 4 times per year. That’s 500 companies a year. To put that in perspective, let’s assume that a typical seed VC makes about one investment per month (12 investments per year). YC represents roughly 40 seed funds worth of competition and makes up at least 10% of the overall institutional seed market.

The problem is that the YC fundraising path tends to be orthogonal to the typical seed VC fundraising path. If you ask most seed managers about YC, they will either say a) that they do very few YC companies because the valuations and deal structures fall outside of their ownership models or b) they have a completely different approach to YC companies that break their standard rules. Either way, YC makes a huge chunk of the market very unpalatable for seed funds that are trying to lead rounds at modest valuations and buy meaningful ownership.

This wouldn’t be that big of a deal if YC only attracted second-tier companies, but that has not been the case. In many ways, YC is the market’s greatest talent scout. And on top of that, alumni keep coming back to YC because of the firm’s incredible network effect in certain segments of the market. If you are a startup selling software that other startups can use, YC is a no-brainer because you get access to a massive network of potential buyers at all maturity stages that are primed to give your product a try. No other seed fund has this level of scale advantage and few, if any, have the same kind of affinity among founders willing to pay it forward towards one another.

The second unstoppable force is, of course, the mega-funds. Some of these funds have programs similar to YC (e.g., A16Z speed run), so they capture an incremental portion of that same part of the market. But more significantly, the mega-funds are systematically targeting consensus founders and alumni, while offering unbeatable terms for initial funding rounds.

By consensus founders, I mean a) a repeat founder with some level of prior success, b) a star player of a top 50 company, or c) a super smart young person who is well networked into the tech elite. If you fit one of these three profiles, a mega-fund will find you and offer terms far beyond what any seed fund would be able to match for your initial financing round. Moreover, the mega-fund will likely get to you much sooner thanks to the scale of their team and the increasingly sophisticated systems they use to mine any signals of talent and traction.

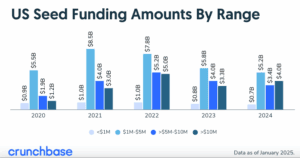

It’s hard to determine how much of the seed market is eaten by this mega-fund activity, but one proxy is round size. Seed funds’ bread and butter tends to be rounds <$5M. Many of the rounds >$5M probably have lifecycle fund participation, and rounds >$10M are almost certainly being led by lifecycle funds. Crunchbase data shows that this proportion of the market has grown considerably, and rounds >$5M account for more than half of seed dollars and about 15% of the market by deal count.

The downsides to taking mega-fund capital are the lack of attention and the potential for signaling risk in the event that these funds don’t lean in heavily to your next round. Although these are true drawbacks, at some point, the terms and amount of capital outweigh the negatives. And often these sorts of founders don’t mind the “go big or go home” mentality given their prior success and their full embrace of the power law narrative (which is point number 3).

So, seed funds are stuck. If you are a highly regarded or proven founder, mega-funds will offer you unbeatable terms. If you are a less proven founder, YC is a very attractive option. How much of the market is captured by these two unstoppable forces is hard to pin down, but I think they represent at least 25%+ of the market and growing. Yes, there are many great founders who don’t choose one of these two paths, but no matter how you slice it, the seed funds are fighting for a smaller piece of the pie.

Power Law as Consensus

Behind the formidable forces of YC and the mega-funds is a more fundamental shift in venture capital and in tech entrepreneurship overall. Over the last 20 years, one of the most controversial and non-intuitive tenets of investing went from being non-consensus to consensus. This is the idea of the power law.

Just for fun, read the notes from Peter Thiel’s CS 183 class from 2012. In this lecture, Peter Thiel, Roelof Botha from Sequoia, and Paul Graham from YC talk about power law dynamics in venture. At the time, the extreme nature of the power law was sort of a secret. Folks didn’t really believe it, and because it’s so counter-intuitive, even those who did failed to fully embrace it.

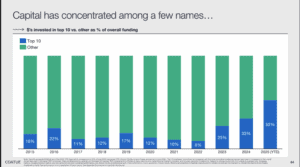

But today, the power law is consensus thinking. The highly skewed distribution of outcomes is clearly evident in early-stage investing, but also in the broader market. On top of this, the market now believes that the level of disparity between the super-outliers and the non-outliers is much, much greater than previously imagined. The best companies aren’t just 10X more valuable, they are 1000X more valuable. These companies aren’t just going to be unicorns, they have the potential to be trillion-dollar companies. And being in the right trillion-dollar company at any point along the journey is way more important than getting into a unicorn at a decent price. This shift in behavior is illustrated in the chart below from Coatue, which shows how dramatically capital is concentrating into a small number of companies.

On top of all this, recent exit markets further support a go-for-broke approach. We are in the midst of a five-year downward trend in M&A, PE buyouts, and IPOs. More concerning is the longer trend of IPOs occurring later for much larger companies. Instead of businesses exiting at $100M ARR in the $1-5B range, typical IPOs today are companies that exit at $500M-$1B in revenue at much higher valuations. This is driven by a multitude of factors that I won’t get into now. But the end result is that we are in an environment where exits are down overall, and the exits that do happen tend to be super-outliers. So investors may as well swing only for grand slams because it’s not like the hit rate of home run outcomes is significantly higher.

So, if you are a scaled player in a market where the power law is the consensus view, there is really only one rational strategy. And that’s to be a price-insensitive index of any company that has the potential to be a super-outlier and then concentrate capital from there. This is what is behind the launch of scaled programs like SpeedRun from A16Z or Arc from Sequoia, and also why you see these very same funds leading $30M+ seed rounds for companies with proven founders or that have any inkling of traction.

The AI Platform Shift

The final factor is actually a force multiplier of the first three topics that I’ve discussed. At this moment in 2025, the entire tech industry is sprinting downhill and head-first into what everyone believes is the most significant technology innovation of our lifetime. Usually, a platform shift is great news for early-stage investors. But if you ask most seed funds, you’ll hear moans of skepticism and frustration. Some very good funds will even say that they are avoiding the AI space altogether despite their belief in the importance of this innovation. This is very, very unusual and further evidence of an investment segment in crisis.

The AI shift presents three challenges to seed funds.

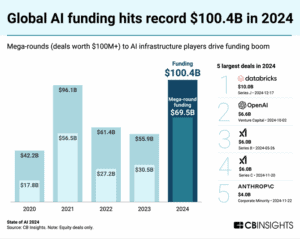

The first is that early in the innovation wave, the value creation tends to occur at the infrastructure or enabling layers. These foundational layers tend to be very capital-intensive and are truly the “sport of kings,” as Bill Gurley has said. Thus far, more of the value has accrued to infrastructure (e.g., Nvidia, Coreweave) and foundation models (e.g., OpenAI), and seed investors were not in a great position to compete in this layer of the stack.

The second is that AI as an opportunity set is consensus. Power law thinking is also consensus. Multiply those together, and all the forces that I’ve discussed get turned up to 11. Yes, seed funds can find their spots investing in AI applications, but anything marginally interesting will be fiercely competitive and valuation expectations are sky-high. We are also in just the first inning of the AI platform shift. There will be multiple boom and bust cycles to endure, and the entire market is entering into these companies at higher-than-normal prices with less-than-normal traction and higher-than-normal risk. It’s a very tricky combination, and one that I believe hurts everyone, but where seed funds are particularly exposed.

The third is that AI is going to disrupt the practice of investing, and most seed funds are poorly positioned to capture this value. Mega-funds have huge AUM and are able to spend many millions of dollars on dedicated engineering and product leadership to leverage AI systems for their own goals. These firms are also armed with large investment teams capable of closing the loop on the last mile where software stops and humans need to take over. If one believes that AI is going to transform every industry, including venture capital, seed funds need to figure out some way to compete against this reality with <1% of the mega-funds’ fee stream.

The End of Seed?

Put this all together, and things look pretty grim for your friendly neighborhood seed investor. Sure, seed investing will continue to exist, and survivorship bias will mean that we’ll always look back at some firms and point to the outliers that are insanely successful. But will that be because of anything predictable like skill, experience, or access? Or will it just be the result of luck?

One hope is that this is just a temporary moment in time. Indeed, every market goes in and out of favor, and this seems like a local minimum for seed investing. But a lot of the forces I’ve described don’t look like they are going to change anytime soon:

Industries mature, and time’s arrow only moves in one direction.

YC isn’t going away anytime soon.

Mega-funds have access to the largest pools of capital in the world and have a lower cost of capital than seed managers, so they aren’t going anywhere.

And does anyone want to bet against the power law or the transformative potential of AI? Maybe, but that’s a pretty scary bet to make.

Hope is not a strategy. Seed VCs are staring extinction in the eye, and we will all have to evolve or die. Is there a reasonable path forward? That’s for my next post.

Blog

Blog